GRAVITY

MAGNUS WALLIN

KALMAR KONSTMUSEUM

MAY 31 – AUGUST 24, 2014

GRAVITY (2013)

Material: Plexiglass, blood powder, epoxy

Dimensions: 10 panels, each 120 x 60 cm

VOLUMES (2014)

Material: books, blood powder, epoxy

Dimensions: 121 x 33 x 26 cm

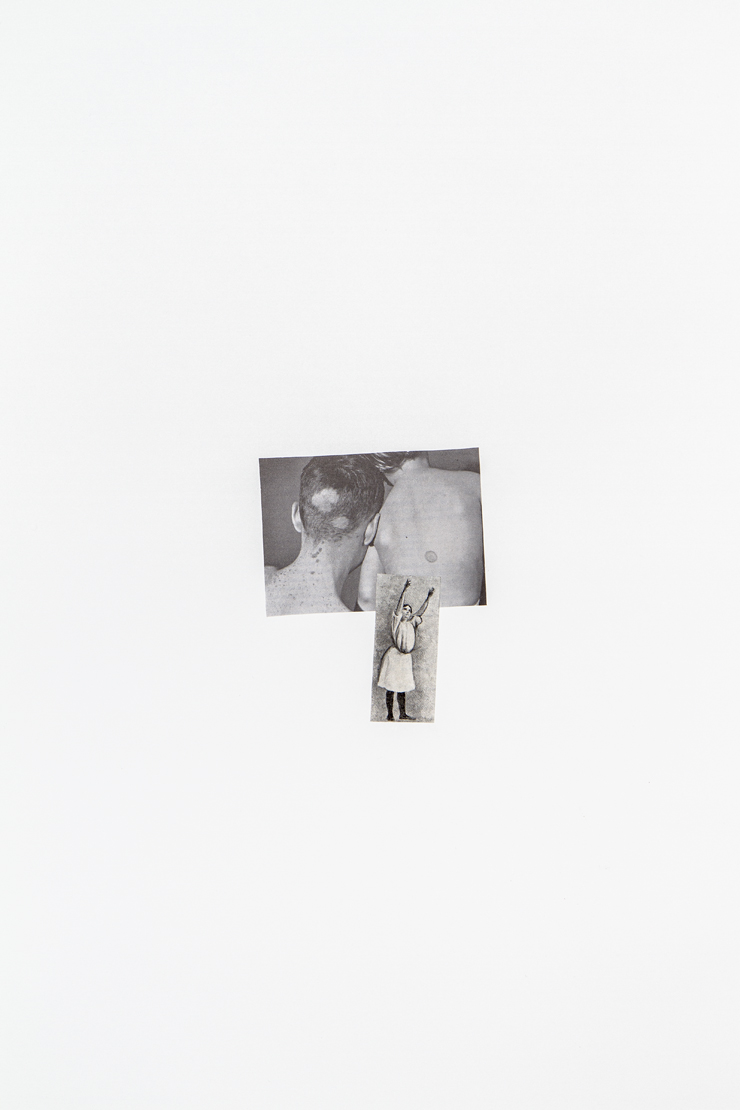

ALBUM (2014)

Dimensions: 69 x 56 cm

Material: Framed collage on paper

CYLINDER (2012)

Material: Blood powder, acrylic, wood, and glossy

Dimensions: 90 x 225 x 90 cm

FILM (2014)

Material: blood powder

Dimensions: 16 x 3,84 m. site-specific

BACKGROUND (2014)

Dimensions: 5 panels, each 300 x 100 cm

Material: Blood powder, acrylic, glossy, wood.

Even before his first animation made him famous, Magnus Wallin had been working with blood. The work Bloody Mary (1994) consisted of five liters of spilled blood on the stairs leading into the Gothenburg City Gallery – as much blood as there is in a human body. I am not sure I have come across this combination of aggressiveness and unshielded pathos anywhere but in Magnus Wallins art. The courage needed to create works of blood must not be underestimated. You almost feel sorry for the work and the artist before even seeing them, as you would for children with such impossible names that they are sure to be bullied at school (at least if I was attending). Blood work will be met by base reactions, they will be ridiculed, called pretentious, unoriginal and bluntly unrefined. One must understand; to be mirrored in blood is not exactly a gift from above. But remember that this reaction is an integral part of the work! Wallin often uses feelings in his work, mostly the negative and unwanted. Two other works from 1994 were to a large degree built on the visitors’ fearful reaction. In I live here the visitor had to press against the entrance wall to avoid the angry German Shepard that the artist had leashed in the room. And in Watch Out the observer was placed between two such barking watch dogs. The reaction of the spectator was obviously a large part of the content of the piece. And this is also the case regarding the blood works. They are almost creating a stage where society is allowed to participate in all its inferiority. Why society rather than the individual? Because the observers in their first reactions are no less alike than two angry cats, they are reduced to a base behavior of the species. And if there is anything that science has shown, it is that the human species is clay in the hands of science, politics, market and religion. Through every quick and annoyed dismissal, the societal body will emerge, but subordinate to the work, as a function of it. The very thought makes one bubble with joy!

The idea of a Magnus Wallin exhibition without a film fascinates me, as if it borders on something you shouldn’t do. I love his films, but what happens if one is simply confronted with his objects, with the primitive rawness inherent in them? It is actually a new situation. The so-called primitive art used, often for ritual purposes, geometry or ornamentation or harmony, to cloak the horrible reality. A bowl, utilized by the Mayans when the entrails of ritually slain humans had to be put somewhere, was so elaborately decorated that the content itself disappeared enough into the background that Henry Moore could find a – for him – decisive inspiration of purely esthetic art. Contrary to that, a slushy blood artist like Hermann Nitsch would have been unable to do his thing without taking the priests very position in an ecstatic ritual that transfigures the blood. Contrary to that, in Wallins work the material itself is the point, or at least not its transformation into esthetics. It begins there, and in the intolerable actuality and primitivism of the objects. Sometimes, his art can appear as taking the position of the victim, in spite of its being really indivisible. On the contrary, the entrails in the bowl as well as the blood in the mirror create a layer of reality that we already share, the position of the body. The experience of this primitivism in his work is almost threatened by his technically and esthetically advanced film art; as a trustworthy gesture, the very refinement of such a film blunts the chock or impact that his objects convey, just as the Mayan bowl did. In this exhibition, this reconciling element will be missing. I’m eager to see the effect. Can the enormous disaster that blood is as soon as it has poured out of the body, really pass by without making the spectators feel the corresponding flow in their own blood? I’m sure it is felt, and blood smells, but the difficulty lies in letting that feeling rise into the conscious mind, without repressing it; retaining it, see with it. Not easy – but then viewing art is not like looking into a store window. A symbol may be tormented (Jesus on the cross); it is a lot harder to accept the very thought that you enjoy looking at a body nailed to a wooden construction in order to suffer; and blood spilled as art – come on! Rather, one cloaks it in refinement, in spite of art often being a question of becoming a mollusk in the viewing, instead of a seal in disguise with a superior culture.

A work such as Cylinder (2012) is a remarkable experience of a body that cannot be circumvented. The precise shape has something artificial and frightening about it, at the same time as blood – one thinks as one walks to the side – really shouldn’t have a shape. It is inevitably frontal, it seems to turn after you, you feel it following you even though your back is turned. Apparently the blood cannot be still. Then, as you turn around, you look at it as it were an alien object from another planet. This must be like what my children feel when they see Tove Jansson’s monster the Groke. In photos of Background (2014) I see bloody, smeared in blood, no blood stained, no drenched in blood, a whole lot of blood it is anyway, crazy much, so much that the work is a disaster in itself. Contrary to the work Gravity (2013) the blood doesn’t seem to be coming out of the bodies themselves, it does not pour from the upper edge. Gravity is in itself bloodless bodies, where the blood seems to appear in the contact with the surroundings, as a feeling of emptiness, sorrow. But here, in Background the blood has come from outside – the canvas has witnessed, or maybe been subjected to it. If this is the background, what then is in the foreground? Me, and my life? Isn’t the blood bound to have originated from the very place in the room where I’m standing? I imagine a remarkable eternity, that must exist in the whole when the sun shines on the blood, and at the same time there is something distinctly past about them. They are quiet, mute – as if the blood itself didn’t scream with the whole hand! Does it? The pattern of the canvases makes them look like a tile wall from a windowless shower room. It is horrible, is all that I, lacking for words for what runs through my body when I see Background; unpleasant, no threatening movements in my stomach, outward, upward, oval. But that is not all: at the same time the associations go through my head: the hygienic environment of the gas chambers – an association given support by the unpleasant showerheads in the wall, Stock (2011), surrounded by single strands of hair as the only remains – slaughterhouses, charcoal drawings of empty rooms for ordered and delivered death. These associations, together with the intrusive blood and its volume, along with the absolute uncomfort of the body (the movement has now reached the throat), the disgust, the revulsion, the longing to faint that is in my body (I’m reporting live now), that’s where the words are not enough…it is revolting. What can I say? It happens now. It is here.

The rawness of the objects, that are not to be veiled by estheticism, is instead broken against the fragility of the collages. They are called Album and even if the pictures aren’t exactly like the ones you come across in family albums, they depict human beings rather than bodies. And we see them with tenderness. The collages are small and the vast emptiness around them makes the picture parts crowd together, like siblings under a vast sky in a desert of snow. Around the whole is a light warm frame. The surroundings are not attacking anymore. A body with four legs and no torso is looking back at me. This too is realism.

by Lars-Erik Hjertström Lappalainen

REVIEW – Magnus Wallin: Gravity, Kalmar Konstmuseum (Dan Jönsson, Dagens Nyheter, 2014)

REVIEW – Gravity, Kalmar Konstmuseum (Martin Arndtzén, Kulturnytt, Swedish Radio, 2014)